Joseph Lister

The Lord Lister | |

|---|---|

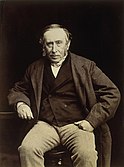

Lister in 1902 | |

| 37th President of the Royal Society | |

| In office 1895–1900 | |

| Preceded by | The Lord Kelvin |

| Succeeded by | Sir William Huggins |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 April 1827 Upton House, West Ham, England |

| Died | 10 February 1912 (aged 84) Walmer, Kent, England |

| Resting place | Hampstead Cemetery, London |

| Spouse | |

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

| Education | University College London |

| Known for | Surgical sterile techniques |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine |

| Institutions | |

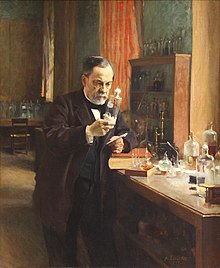

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, OM, PC, FRS, FRCSE, FRCPGlas, FRCS (5 April 1827 – 10 February 1912[1]) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and pioneer of antiseptic surgery[2] and preventive healthcare.[1] Joseph Lister revolutionised the craft of surgery in the same manner that John Hunter revolutionised the science of surgery.[3]

From a technical viewpoint, Lister was not an exceptional surgeon,[2] but his research into bacteriology and infection in wounds revolutionised surgery throughout the world.[4]

Lister's contributions were four-fold. Firstly, as a surgeon at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary, he introduced carbolic acid (modern-day phenol) as a steriliser for surgical instruments, patients' skins, sutures, surgeons' hands, and wards, promoting the principle of antiseptics. Secondly, he researched the role of inflammation and tissue perfusion in the healing of wounds. Thirdly, he advanced diagnostic science by analyzing specimens using microscopes. Fourthly, he devised strategies to increase the chances of survival after surgery. His most important contribution, however, was recognising that putrefaction in wounds is caused by germs, in connection to Louis Pasteur's then-novel germ theory of fermentation.[a][6]

Lister's work led to a reduction in post-operative infections and made surgery safer for patients, leading to him being distinguished as the "father of modern surgery".[7]

Early life

[edit]Lister was born to a prosperous, educated Quaker family in the village of Upton, then near but now in London,[8] England. He was the fourth child and second son of four sons and three daughters[9] born to gentleman scientist and wine merchant Joseph Jackson Lister and school assistant Isabella Lister née Harris.[10][11] The couple married in a ceremony held in Ackworth, West Yorkshire on 14 July 1818.[12]

Lister's paternal great-great-grandfather, Thomas Lister was the last of several generations of farmers who lived in Bingley in West Yorkshire.[13] Lister joined the Society of Friends as a young man and passed his beliefs on to his son, Joseph Lister.[13] He moved to London in 1720 to open a tobacconist's shop[13] in Aldersgate Street in the City of London.[14] His son, John Lister, was born there. Lister's grandfather was apprenticed to watchmaker, Isaac Rogers,[15] in 1752 and followed that trade on his own account in Bell Alley, Lombard Street from 1759 to 1766. He then took over his father's tobacco business,[13] but gave it up in 1769 in favour of working at his father-in-law Stephen Jackson's business as a wine-merchant at No 28 Old Wine and Brandy Values on Lothbury Street, opposite Tokenhouse Yard.[16]

His father was a pioneer in the design of achromatic object lenses for use in compound microscopes[8] He spent 30 years perfecting the microscope, and in the process, discovered the Law of Aplanatic Foci,[17] building a microscope where the image point of one lens coincided with the focal point of another.[8] Up until that time, the best higher magnification lenses produced an excessive secondary aberration known as a coma, which interfered with normal use.[8] It was considered a major advance that elevated histology into an independent science.[18] By 1832, Lister's work had built a reputation sufficient to enable his being elected to the Royal Society.[19][20] His mother, Isabella, was the youngest daughter of master mariner Anthony Harris.[21] Isabella worked at the Ackworth School, a Quaker school for the poor, assisting her widowed mother, the superintendent of the school.[21]

The eldest daughter of the couple was Mary Lister. On 21 August 1851, she married the barrister Rickman Godlee[22] of Lincoln's Inn and the Middle Temple, who belonged to the Friends meeting house in Plaistow.[23] The couple had six children. Their second child was Rickman Godlee, a neurosurgeon who became Professor of Clinical Surgery at the University College Hospital[22] and surgeon to Queen Victoria. He became Lister's biographer in 1917.[22] The eldest son of Joseph and Isabella Lister was John Lister, who died of a painful brain tumour.[24] With John's death, Joseph became the heir of the family.[24] The couple's second daughter was Isabella Sophia Lister, who married Irish Quaker Thomas Pim[25] in 1848. Lister's other brother William Henry Lister died after a long illness.[9] The youngest son was Arthur Lister, a wine merchant, botanist and lifelong Quaker, who studied Mycetozoa. He worked alongside his daughter Gulielma Lister to produce the standard monograph on Mycetozoa. By 1898, Lister's work had built a reputation sufficient to enable his election to the Royal Society.[26] Gulielma Lister, a talented artist, later updated the standard monograph with colour drawings. Her work built a reputation sufficient to be elected a fellow of the Linnean Society in 1904. She becoming its vice-president in 1929.[27] The couple's last child was Jane Lister; she married widower Smith Harrison, a wholesale tea merchant.[28]

After their marriage, the Listers lived at 5 Tokenhouse Yard in Central London for three years until 1822, where they ran a port wine business in partnership with Thomas Barton Beck.[29] Beck was the grandfather of the professor of surgery and proponent of the germ theory of disease, Marcus Beck,[30] who would later promote Lister's discoveries in his fight to introduce antiseptics.[31] In 1822, Lister's family moved to Stoke Newington.[32] In 1826, the family moved to Upton House, a long low Queen Anne style mansion[32] that came with 69 acres of land.[33] It had been rebuilt in 1731, to suit the style of the period.[34]

Education

[edit]School

[edit]As a child, Lister had a stammer and this was possibly why he was educated at home until he was eleven.[35] Lister then attended Isaac Brown and Benjamin Abbott's Academy, a private[36] Quaker school in Hitchin, Hertfordshire.[37] When Lister was thirteen,[35] he attended Grove House School in Tottenham, also a private Quaker School[37] to study mathematics, natural science, and languages. His father was insistent that Lister received a good grounding in French and German, in the knowledge he would learn Latin at school.[38] From an early age, Lister was strongly encouraged by his father[8] and would talk about his father's great influence later in life, particularly in encouraging him in his study of natural history.[35] Lister's interest in natural history led him to study bones and to collect and dissect small animals and fish that were examined using his father's microscope[19] and then drawn using the camera lucida technique that his father had explained to him,[30] or sketched.[37] His father's interests in microscopical research developed in Lister the determination to become a surgeon[19] and prepared him for a life of scientific research.[8] None of Lister's relatives were in the medical profession. According to Godlee, the decision to become a physician seemed to be an entirely spontaneous decision.[39]

In 1843 his father decided to send him to university. As Lister was unable to attend either University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge owing to the religious tests that effectively barred him,[8] he decided to apply to the non-sectarian University College London Medical School (UCL), one of only a few institutions in Great Britain that accepted Quakers at that time.[40] Lister took the public examination in the junior class of botany, a required course that would enable him to matriculate.[41] Lister left school in the spring of 1844 when he was seventeen.[37]

University

[edit]In 1844, just before Lister's seventeenth birthday, he moved to an apartment at 28 London Road that he shared with Edward Palmer, also a Quaker.[42] Between 1844 and 1845, Lister continued his pre-matriculation studies, in Greek, Latin and natural philosophy.[43] In the Latin and Greek classes, he won a "Certificate of Honour".[44] For the experimental natural philosophy class, Lister won first prize and was awarded a copy of Charles Hutton's "Recreations in Mathematics and Natural Philosophy".[45]

Although his father wanted him to continue his general education,[46] the university had demanded since 1837, that each student obtain a Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree before commencing medical training.[47] Lister matriculated in August 1845, initially studying for a BA in classics.[48] Between 1845 and 1846, Lister studied the mathematics of natural philosophy, mathematics and Greek earning a "Certificate of Honour" in each class.[44] Between 1846 and 1847, Lister studied both anatomy and atomic theory (chemistry) and won a prize for his essay.[44] On 21 December 1846, Lister and Palmer attended Robert Liston's famous operation where ether was applied by Lister's classmate, William Squire to anaesthetise a patient for the first time.[49][50] On 23 December 1847, Lister and Palmer moved to 2 Bedford Place and were joined by John Hodgkin, the nephew of Thomas Hodgkin who discovered Hodgkin lymphoma.[51] Lister and Hodgkin had been school friends.[51]

In December 1847, Lister graduated with a degree of Bachelor of Arts 1st division, with a distinction in classics and botany.[8] While he was studying, Lister suffered from a mild bout of smallpox, a year after his elder brother died of the disease.[8] The bereavement combined with the stress of his classes led to a nervous breakdown in March 1848.[52] Lister's nephew Godlee used the term to describe the situation and is perhaps indicative that adolescence was just as difficult in 1847, as it is now.[8] Lister decided to take a long holiday[36] to recuperate and this delayed the start of his studies.[36] In late April 1848, Lister visited the Isle of Man with Hodgkin and by 7 June 1848, he was visiting Ilfracombe.[53] At the end of June, Lister accepted an invitation to stay in the home of Thoman Pim, a Dublin Quaker. Using it as his base, Lister travelled throughout Ireland.[54] On 1 July 1848, Lister received a letter full of warmth and love from his father where his last meeting was "...sunshine after a refreshing shower, following a time of cloud" and advised him to "cherish a pious cheerful spirit, open to see and to enjoy the bounties and the beauties spread around us :—not to give way to turning thy thoughts upon thyself nor even at present to dwell long on serious things".[36] From 22 July 1848, for more than a year, the record is blank.[55]

Medical student

[edit]Lister registered as a medical student in the winter of 1849[56] and became active in the University Debating Society and the Hospital Medical Society.[30] In the autumn of 1849, he returned to college with a microscope given to him by his father.[50] After completing courses in anatomy, physiology and surgery, he was awarded a "Certificate of Honours", winning the silver medal in anatomy and physiology and a gold medal in botany.[41]

His main lecturers were John Lindley professor of botany, Thomas Graham professor of chemistry, Robert Edmond Grant professor of comparative anatomy, George Viner Ellis professor of anatomy and William Benjamin Carpenter professor of medical jurisprudence.[36] Lister often spoke highly of Lindley and Graham in his writings, but Wharton Jones professor of ophthalmic medicine and surgery, and William Sharpey professor of physiology, exercised the greatest influence on him.[36] He was greatly attracted by Dr. Sharpey's lectures, which inspired in him a love of experimental physiology and histology that never left him.[57]

Thomas Henry Huxley praised Wharton Jones for the method and quality of his physiology lectures.[36] As a clinical scientist working in physiological sciences, he was foremost in the number of discoveries he made.[36] He was also considered a brilliant ophthalmic surgeon, his main field.[36] He conducted research into the circulation of blood and the phenomena of inflammation, carried out on the frog's web[b] and the bat's wing, and no doubt suggested this method of research to Lister.[36] Sharpey was called the father of modern physiology as he was the first to give a series of lectures on the subject.[36] Prior to that the field had been considered part of anatomy.[36] Sharpey studied at Edinburgh University, then went to Paris to study clinical surgery under French anatomist Guillaume Dupuytren and operative surgery under Jacques Lisfranc de St. Martin. Sharpey met Syme while in Paris and became the two became life-long friends.[36] After he moved to Edinburgh he taught anatomy with Allen Thomson as his physiological colleague. He left Edinburgh in 1836, to become the first Professor of Physiology.

Clinical instruction

[edit]

To qualify for his degree, Lister had to complete two years of clinical instruction,[47] and began his residency at University College Hospital in October 1850.[56] as an intern and then house physician to Walter Hayle Walshe,[30] professor of pathological anatomy and author of the 1846 study, The Nature and Treatment of Cancer.[59] Lister in 1850 again received "Certificates of Honours" and won two gold medals in anatomy and a silver medal each in surgery and medicine.[41]

In his second year in 1851, Lister became first a dresser in January 1851[60] then a house surgeon to John Eric Erichsen in May 1851.[50] Erichsen was professor of surgery[7] and author of the 1853 Science and Art of Surgery,[61] described as one of the most celebrated English-language textbooks on surgery.[60] The book went through many editions; Marcus Beck edited the eighth and ninth, adding Lister's antiseptic techniques and Pasteur and Robert Koch's germ theory.[62]

Lister's first case notes were recorded on 5 February 1851. As a dresser, his immediate superior was Henry Thompson, who recalled "..a shy Quaker...I remember that he had a better microscope than any man in the college".[63]

Lister had only just begun working in his role as dresser to Erichsen in January 1851, when an epidemic of erysipelas broke out in the male ward.[55] An infected patient from an Islington workhouse was left in Erichsen's surgical ward for two hours.[55] The hospital had been free of infection but within days there were twelve cases of infection and four deaths.[55] In his notebook, Lister stated that the disease was a form of surgical fever, and particularly noted that recent surgical patients were infected the worst, but that those with older surgeries with suppurating wounds, 'mostly escaped'.[55] It was while Lister worked for Erichsen, that his interest in the healing of wounds began.[7] Erichsen was a miasmist who thought the wounds became infected from miasmas from the wound itself that caused a noxious form of "bad air" that spread to other patients in the ward.[7] Erichsen believed that seven patients with an infected wound had saturated of the ward with "bad air", which spread to cause gangrene.[7] However Lister saw that some wounds, when debrided and cleaned, would sometimes heal. He believed that something in the wound itself was at fault.[7]

When he became a house surgeon, Lister had patients put in his charge.[60] For the first time, he came into contact face-to-face with various forms of blood-poisoning diseases like pyaemia[64] and hospital gangrene, which rots living tissue with a remarkable rapidity.[60][65] While examining in an autopsy an excision of the elbow of a little boy who had died of pyaemia, Lister noticed that a thick yellow-pus was present at the seat of the humerus bone, and distended the brachial and axillary veins.[66] He also noticed that the pus advanced in the reverse direction along the veins, bypassing the valves in the veins.[66] He also found suppuration in a knee-joint and multiple abscesses in the lungs.[66] Lister knew that Charles-Emmanuel Sédillot had discovered that multiple abscesses in the lungs were caused by introducing pus into the veins of an animal. At the time he could not explain the facts but believed the pus in the organs had a metastatic origin.[66] On 2 October 1900, during The Huxley Lecture, Lister described how his interest in the germ theory of disease and how it applied to surgery began with his investigation into the death of that little boy.[67]

There was an epidemic of gangrene during his surgeoncy. The treatment method was to chloroform the patient, scrape the soft slough off and burn the necrotic flesh away with mercury pernitrate[60] Occasionally the treatment would succeed, but when a grey film appeared at the edges of the wound, it presaged death.[60] In one patient, the repeated treatment failed several times, so Erichsen amputated the limb, which healed fine.[68] Lister recognised was that the disease was a "local poison" and probably parasitic in nature.[68] He examined the diseased tissues under his microscope. He saw peculiar objects that he could not identify, as he had no frame of reference to draw conclusions from these observations.[60] In his notebook he recorded:

I imagined they might be the materies morbi in the form of some kind of fungus.[c]

Lister wrote two papers on the epidemics; but both were lost: Hospital gangrene[50] and Microscope. They were read to the Student Medical Society at UCL.[50]

Lister's first operation

[edit]On 26 June 2013, medical historian Ruth Richardson and orthopaedic surgeon Bryan Rhodes published a paper in which they described their discovery of Lister's first operation, made while both were researching his career.[50] At 1 pm on 27 June 1851, Lister, a second-year medical student working at a casualty ward in Gower Street, conducted his first operation. Julia Sullivan, a mother of eight grown children, had been stabbed in the abdomen by her husband, a drunk and ne'er-do-well, who was taken into custody.[69] On 15 September 1851, Lister was called as a witness to the husband's trial at the Old Bailey.[69] His testimony helped convict the husband, who was transported to Australia for 20 years.[69]

About a yard of small intestine about eight inches across, damaged in two places, protruded from the woman's lower abdomen, which had three open wounds.[50] After cleaning the intestines with blood-warm water, Lister was unable to place them back into the body, so he decided to extend the cut.[50] then placed them back into the abdomen, and sewed and sutured the wounds shut.[50] He administered opium to induce constipation and enable the intestines to recover. Sullivan recovered her health.[50] This was a full decade before his first public operation in the Glasgow Infirmary.[50]

This operation was missed by historians.[50] Liverpool consultant surgeon John Shepherd, in his essay on Lister, Joseph Lister and abdominal surgery, written in 1968,[70] failed to mention the operation, and instead started his account from the 1860s onwards. He apparently was unaware of this surgery.[50]

Microscope experiments 1852

[edit]Observations on the Contractile Tissue of the Iris

[edit]Lister's first paper,[71] written while he was still at university,[72] was published in the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science in 1853.[73]

On 11 August 1852, Lister attended an operation at University College Hospital by Wharton Jones,[74] who presented him with a fresh slice of human iris. Lister took the opportunity to study the iris.[71] He reviewed existing research and studied tissue from a horse, a cat, a rabbit and a guinea pig as well as six surgical specimens from patients who had undergone eye surgery.[75] Lister was unable to complete his research to his satisfaction, due to his need to pass his final examination. He offered an apology in the paper:

My engagements do not allow me to carry the inquiry further at present; and my apology for offering the results of an incomplete investigation is that a contribution tending, in however small a degree, to extend our acquaintance with so important an organ as the eye, or to verify observations that may be thought doubtful, may probably be of interest to the physiologist.[72]

The paper advanced the work of Swiss physiologist Albert von Kölliker, demonstrating the existence of two distinct muscles, the dilator and sphincter in the iris.[19] This corrected the convictions of previous researchers that there was no dilator pupillae muscle.[75]

Observations on the Muscular Tissue of the Skin

[edit]His next paper, an investigation into goose bumps,[76][77] was published on 1 June 1853 in the same journal.[78] Lister was able to confirm Kölliker's experimental finding that in humans the smooth muscle fibres are responsible for making hair stand out from the skin, in contrast to other mammals, whose large tactile hairs are associated with striated muscle.[75] Lister also demonstrated a new method of creating histological sections from the tissue of the scalp.[79]

Lister's microscopy skills were so advanced that he was able to correct the observations of German histologist Friedrich Gustav Henle, who mistook small blood vessels for muscle fibres.[80] In each of the papers, he created camera lucida drawings so accurate that they could be used to scale and measure the observations.[78]

Both papers attracted significant attention in Britain and abroad.[81] Naturalist Richard Owen, an old friend of Lister's father, was particularly impressed by them.[81] Owen contemplated recruiting Lister for his department and forwarded him a thank-you letter on 2 August 1853.[81] Kölliker was particularly pleased with the analysis that Lister had formulated. Kölliker made many trips to Britain, and eventually met Lister. They became life-long friends.[81] Their close friendship was described in a letter by Kölliker on 17 November 1897, that Rickman Godlee chose to use to illustrate their relationship.[82] Kölliker sent a letter to Lister when he was president of the Royal Society, congratulating him on receiving the Copley medal, fondly remembering old friends who had died, and celebrating his time in Scotland with Syme and Lister. Kölliker was 80 years old at the time.[82]

Graduation

[edit]Lister graduated with a Bachelor of Medicine with honours in the autumn of 1852.[73] During his final year, Lister won several prestigious awards heavily contested among the student body of London teaching hospitals.[83] He won the Longridge Prize

For the greatest proficiency evinced during the three years immediately preceding, on the Sessional Examinations for Honours in the classes of the Faculty of Medicine of the College; and for creditable performance of duties of offices at the Hospital

that included a £40 stipend.[83] He was also awarded a gold medal in structural and physiological botany.[83][44] Lister won two of the four available gold medals in anatomy and physiology as well as surgery, which came with a scholarship of £50 a year for two years, for his second examination in medicine.[83] In the same year, Lister passed the examination for the fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons,[73] bringing to a close nine years of education.[73]

Sharpey advised Lister to spend a month at the medical practice of his lifelong friend James Syme in Edinburgh and then visit medical schools in Europe for a longer period for training.[84] Sharpey himself had been taught first in Edinburgh and later in Paris. Sharpey had met Syme, a teacher of clinical surgery widely considered the best surgeon in the United Kingdom[85] while he was in Paris.[86] Sharpey had gone to Edinburgh in 1818,[87] along with many other surgeons since, due to the influence of John Hunter.[85] Hunter had taught Edward Jenner, seen as the first surgeon to take a scientific approach to the study of medicine, known as the Hunterian method[88] Hunter was an early advocate for careful investigation and experimentation,[89] using the techniques of pathology and physiology to give himself a better understanding of healing than many of his colleagues.[85] For example, his 1794 paper, A treatise on the blood, inflammation and gun-shot wounds[89] was the first systematic study of swelling,[85] discovering that inflammation was common to all diseases.[90] Due to Hunter, surgery, then practised by hobbyists or amateurs, became a true scientific profession.[85] As the Scottish universities taught medicine and surgery from a scientific viewpoint, surgeons who wished to emulate those techniques travelled there for training.[91] Scottish universities had several other features that distinguished them from those in the south.[92] They were inexpensive and did not require religious admissions tests, and thus attracted the most scientifically progressive students in Britain.[92] The most important differentiator was that medical schools in Scotland had evolved from a scholarly tradition, where English medical schools relied on hospitals and practice.[92] Experimental science had no practitioners at English medical schools and while Edinburgh University medical school was large and active at the time, southern medical schools were generally moribund, and their laboratory space and teaching materials inadequate.[92] English medical schools also tended to view surgery as manual labour, not a respectable calling for a gentleman academic.[92]

Surgical profession 1854

[edit]Before Lister's studies of surgery, many people believed that chemical damage from exposure to "bad air", or miasma, was responsible for infections in wounds.[93] Hospital wards were occasionally aired out at midday as a precaution against the spread of infection via miasma, but facilities for washing hands or a patient's wounds were not available. A surgeon was not required to wash his hands before seeing a patient; in the absence of any theory of bacterial infection, such practices were not considered necessary. Despite the work of Ignaz Semmelweis and Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., hospitals practised surgery under unsanitary conditions. Surgeons of the time referred to the "good old surgical stink" and took pride in the stains on their unwashed operating gowns as a display of their experience.[94]

Edinburgh 1853–1860

[edit]James Syme

[edit]Syme, a well-established clinical lecturer at Edinburgh University for more than two decades before he met Lister,[95] was considered the boldest and most original surgeon then living in Great Britain.[96] He became a surgical pioneer during his career, preferring simpler surgical procedures, as he detested complexity,[95] in the era that immediately preceded the introduction of anaesthesia.[97]

In September 1823, at the age of 24, Syme made a name for himself by first performing an amputation at the hip-joint,[97][98] the first in Scotland. Considered the bloodiest operation in surgery, Syme completed it in less than a minute,[95][97] as speed was essential at that time, before anaesthesia. Syme became widely known and acclaimed for developing a surgical operation that became known as Syme amputation, an amputation at the ankle where the foot is removed and the heel pad is preserved.[99] Syme was considered a scientific surgeon, as evidenced by his paper On the Power of the Periosteum to form New Bone,[97] and became one of the first advocates of antiseptics.

Arrival in Edinburgh

[edit]In September 1853, Lister arrived in Edinburgh bearing letters of introduction from Sharpey to Syme.[100] Lister was anxious about his first appointment but decided to settle in Edinburgh after meeting Syme, who embraced him with open arms, invited him to dinner, and offered him an opportunity to assist him in his private operations.[84]

Lister was invited to Syme's house Millbank in Morningside (now part of Astley Ainslie Hospital),[101] where he met, amongst others, Agnes Syme, Syme's daughter from another marriage and granddaughter of physician Robert Willis.[102][103] While Lister thought that Agnes was not conventionally pretty, he admired her quickness of mind, her familiarity with medical practice, and her warmth.[103] He became a frequent visitor to Millbank and met a much wider group of eminent people than he would have in London.[104]

In the same month, Lister began work as an assistant to Syme at the University of Edinburgh[84] In a letter to his father, Lister expressed surprise at the size of the infirmary and spoke about his impressions of Syme, "..is larger than I expected to find it; there are 200 Surgical beds, and a large number in other departments. At University College Hospital there were only about 60 Surgical beds, so altogether a prospect appears to be opening of a very profitable stay here. ...Syme is, I suppose, the first of British surgeons, and to observe the practice and hear the conversation of such a man is of the greatest possible advantage".[105] By October 1853, Lister decided to spend the winter in Edinburgh. Syme was so impressed by Lister, that after a month Lister became Syme's supernumerary house surgeon at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh[106] and his assistant in his private hospital at Minto House in Chambers Street.[101] As house surgeon, Lister assisted Syme during every operation, taking notes.[106] It was a much-coveted position[30] and gave Lister the option of choosing which of the ordinary cases he would attend.[19] During this period, Lister presented a paper at the Royal Edinburgh Medico-Chirurgical Society on the structure of cancellous exostoses that had been removed by Syme, demonstrating that the method of ossification of these growths is the same as that which occurs in epiphyseal cartilage.[107]

In September 1854, Lister's house surgeoncy appointment was finished.[108] With the prospect of being out of a job, he spoke to his father about seeking a position at the Royal Free Hospital in London.[108] However, Sharpey had written to Syme warning him that it was unlikely that Lister would be welcome at the Royal Free as he would have likely eclipsed Thomas H. Wakley, whose father held considerable sway at the hospital.[109] Lister then made plans to tour Europe for a year.[110] However, an opportunity presented itself with the death of noted infirmary surgeon and surgical lecturer at the Edinburgh Extramural School of Medicine Richard James Mackenzie.[111] Mackenzie had been seen as a successor to Syme[111] but had contracted cholera in Balbec in Scutari, Istanbul, while on a four-month volunteer sabbatical as field surgeon to the 79th Highlanders during the Crimean War.[30] Lister proposed to Syme that he take over Mackenzie's position and become assistant surgeon to Syme.[110] Syme initially rejected the idea, as Lister was not licensed to operate in Scotland, but later warmed to the idea.[110] In October 1854, Lister was appointed as a lecturer[112]Lister successfully transferred the lease held by Mackenzie at his lecture room at 4 High School Yards, to himself. On 21 April 1855, Lister was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh[113] and two days later rented a home at 3 Rutland Square.[30] In June 1855, Lister made a hurried trip to Paris to take a course on operative surgery on the dead body and returned in June.[113]

Extramural lecturing

[edit]

On 7 November 1855, Lister gave his first extramural lecture on the "Principles and Practice of Surgery", in a lecture theatre at 4 High School Yards[114] known as Old Jerusalem, directly located across from the infirmary.[115] His first lecture was read from 21 pages of foolscap folio.[116] Lister's first lectures were based on notes, either read or spoken, but over time he used notes less and less,[115] becoming extempore in his speech, slowly and deliberately forming his argument as he went along.[117] With this deliberate way of speaking, he managed to overcome a slight, occasional stammer which in his early days had been more pronounced.[117]

His first student was John Batty Tuke,[115] in a class of nine or ten, mostly consisting of dressers.[116] Within a week, twenty-three people had joined.[116] In the next year, only eight folk turned up. In the summer of 1858, Lister had the ignominious experience of reading his lecture to a single student, who arrived ten minutes late. Seven more students arrived later.[118]

His first lecture focused on the concept of surgery, giving a definition of disease that linked it to the Hippocratic Oath.[119] He then explained that surgery could have more benefits than medicine, which could only comfort the patient at best. He then explained the attributes a good surgeon should exhibit, before finishing the lecture by recommending Syme's book "Principles of Surgery". Lister completed 114 lectures that followed a standard syllabus. Lecture VII described his earliest experiment on inflammation, where he put mustard on his arm and watched the results. Lectures IV to IX dealt with the circulation of blood. Inflammation was discussed in lectures X to XIII. The second half of the course dealt with clinical surgery. For the last four days, he gave two lectures a day, to complete the event before his wedding, with the first course ending on 18 April 1856.[120] In the summer of 1858, Lister started a second, completely separate course, where he lectured on surgical pathology and operative surgery.[121]

Marriage

[edit]By mid-summer 1854, Lister had started to court Agnes Syme.[122] Lister wrote to his parents about his love but they worried about the union, particularly since he was Quaker and Agnes had given no indication that she would change her denomination.[123] At that time when a Quaker married a person of another denomination, it was considered as marrying out of the society.[112] Lister was determined to marry Agnes and sent a further letter to his father, asking him if his financial support would continue should Lister and Agnes marry. Lister's father replied that Agnes not being in the Society of Friends would not affect his pecuniary arrangements[54] and offered his son extra money to buy furniture and suggested that Syme would offer a dowry and that he would negotiate with Syme directly on it.[54] His father suggested that Lister voluntarily resign from the Society of Friends.[54] Lister made up his mind and subsequently left the Quakers to become a Protestant, later joining the congregation of the Saint Paul's Episcopal Church in Jeffrey Street, Edinburgh.[124] In August 1855, Lister became engaged to Agnes Syme[30] and on 23 April 1856 married her in the drawing room of Millbank, Syme's house in Morningside.[125] Agnes's sister stated that this was out of consideration of any Quaker relations.[54] Only the Syme family were present.[126] The Scottish physician and family friend John Brown toasted the couple after the reception.[54]

The couple spent a month at Upton and the Lake District,[125] followed by a three-month tour of the leading medical institutes in France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy.[127] They returned in October 1856.[128] By this time, Agnes was enamoured with medical research and became Lister's partner in the laboratory for the rest of her life.[126] When they returned to Edinburgh, the couple moved into a rented house at 11 Rutland Street in Edinburgh.[128] The house was situated over three floors with a study on the first floor, that was converted into a consulting room for patients and a room with hot and cold taps on the second floor that became his laboratory.[54] The Scottish surgeon Watson Cheyne, who was almost a surrogate son to Lister, stated after his death that Agnes had entered into her work wholeheartedly, had been his only secretary, and that they discussed his work on an almost equal footing.[55]

Lister's books are full of Agnes' careful handwriting.[55] Agnes would take dictation from Lister for hours at a stretch. Spaces would be left blank amongst the reams of Agnes' handwriting for small diagrams, that Lister would create using the camera lucida technique and Agnes would later paste in.[55]

Assistant surgeoncy

[edit]On 13 October 1856, he was unanimously elected to the position of Assistant Surgeoncy at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary.[128] In 1856 he was also elected a member of the Harveian Society of Edinburgh.[129][130]

Contributions to physiology and pathology 1853–1859

[edit]Between 1853 and 1859 in Edinburgh, Lister conducted a series of physiological and pathological experiments His approach was rigorous and meticulous in both measurement and description.[131] Lister was clearly aware of the latest advances in physiological research in France, Germany, and other European countries[8] and maintained an ongoing discussion of his observations and results with other leading physicians in his peer group including Albert von Kölliker, Wilhelm von Wittich, Theodor Schwann, and Rudolf Virchow[131] and ensured he correctly cited their work.

Lister's primary instrument of research was his microscope and his primary research subjects were frogs. Before his honeymoon, the couple had visited his uncle's house in Kinross.[132] Lister took his microscope and captured several frogs, intending to use them in the study of inflammation, but they escaped.[132] When he returned from his honeymoon, he used frogs captured from Duddingston Loch in his experiments.[133] Lister carried out his experiments in his laboratory and in the veterinary college abattoir, on animals that were either dead or chloroformed and pithed, to deprive it of sensation.[134] He also used bats, sheep, cats, rabbits, oxen and horses in his experiments.[134] Lister's tirelessness in his pursuit of knowledge was illustrated by his assistant Thomas Annandale, who stated:

I confess that on more than one occasion our patience was a little tried by the long hours were thus engaged, and more particularly when the dinner hour was many hours overdue, but no one could work with Mr. Lister without imbibing some of his enthusiasm.[135]

These experiments resulted in the publication of eleven papers between 1857 and 1859.[131] They included the study of the nervous control of arteries, the earliest stages of inflammation, the early stages of coagulation, the structure of nerve fibres, and the study of the nervous control of the gut with reference to sympathetic nerves.[131] He continued these experiments for three years until he was appointed to a position at the University of Glasgow.[136]

1855: Beginning of inflammation research

[edit]In a letter dated 16 September 1855, Lister recorded the beginnings of his research into inflammation, six weeks before his lectures were to begin.[137] Later in life, Lister stated that he considered his research into inflammation to have been an "essential preliminary" to his conception of the antiseptic principle and insisted that these early findings be included in any memorial volume of his work.[138] In 1905, when he was seventy-eight years old, he wrote,

If my works are read when I am gone, these will be the ones most highly thought of.[139]

Inflammation is defined by four symptoms, heat, redness, swelling and pain.[140] Surgeons prior to Lister saw it as the signal for the arrival of suppuration or putrefaction, local or general infection.[141] As the germ theory of disease had not yet been discovered, the concept of infection did not yet exist.[141] However, Lister knew that slowing of the blood through the capillaries seemed to precede inflammation.[133] Joseph Jackson Lister had written a paper with Thomas Hodgkin that described how blood cells behaved prior to a clot, i.e. specifically how the concave cells fitted themselves together into stacks.[141] Lister knew that to observe the next step, it was important that the tissue remain alive so the blood vessels could be observed through the microscope.[141]

In September 1855, Lister's first experiment was on the artery of a frog viewed under his microscope, subjected to a water droplet of differing temperatures, to determine the early stage of inflammation.[142][143] He initially applied a water droplet at 80 °F (27 °C) which caused the artery to contract for a second and the flow to cease, then dilate as the area turned red and the flow of blood increased.[144] He progressively increased the temperature to 200 °F (93 °C). The blood slowed down and then coagulated.[144] He continued the experiment on the wing of a chloroformed bat to widen his research focus.[145] Lister concluded that the contraction of the vessels led to the exclusion of blood cells from the capillaries, not their arrest, and that blood serum continued to flow. This was his first independent discovery.[119]

The experiments ceased between October 1855 and continued in September 1856 when the couple moved into Rutland Square.[146] Lister started with mustard as an irritant, then Croton oil, acetic acid, oil of Cantharidin and chloroform and many others.[146] These experiments led to the production of three papers. His first paper grew out of the need to prepare for these extramural lectures and had begun the year before, continuing in development for six weeks after he moved into Rutland Street.[147] The early paper, titled: "On the early stages of inflammation as observed in the Foot of a Frog" was read to the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh on 5 December 1856. The last third was read out extempore.[147]

1856 Beginning of coagulation research

[edit]Lister also conducted research into the process of coagulation during this period.[148] He had observed inflammation in certain cases of septicaemia that affected the blood vessel's lining, and led to intravascular blood clotting,[149] which led to putrefaction and secondary haemorrhage.[150] A simple experiment in December 1856 described by Agnes, where he pricked his own finger to observe the process of coagulation.[148] led to five physiology papers on coagulation between 1858[121] and 1863.[67]

Several competing theories explained the occurrence of a blood clot, and although the theories were largely abandoned, it was still thought that blood contained a liquifying agent,[151] i.e. fibrin held in a solution of ammonia[152] that became known as the "Ammonia theory".[150]

In 1824, Charles Scudamore had proposed carbonic acid as the solution.[153] The prevailing theory was from Benjamin Ward Richardson, who won the 1857 Astley Cooper triennial prize for an essay where he postulated that blood remained liquid due to the presence of ammonia. In the same year, Ernst Wilhelm von Brücke proposed that the vital actions of the vessels inhibited the blood's natural tendency to coagulate.[154]

1856 On the minute structure of involuntary muscle fibre

[edit]Lister's third paper,[155][156] published in 1858 in the same journal and read before the Royal Society of Edinburgh on 1 December 1856,[155] concerned the histology and function of the minute structures of involuntary muscle fibres.[75] The experiment, conducted in the autumn of 1856,[157] was designed to confirm Kölliker's observations on the structure of individual muscle fibres.[75] Kölliker's description had been criticised, as he had used needles to separate the tissue to observe individual cells, and his critics said that he had observed artefacts from the experiment rather than real muscle cells.[147] Lister proved conclusively that the muscle fibres of blood vessels, described by Lister as slightly flattened and elongated,[155] were similar to those found by Kölliker in pig intestine, but wrapped spirally and individually around the innermost membrane.[157] He stated that the variations in shape, from long tubular bodies with pointed ends and elongated nuclei to short "spindles" with squat nuclei, represented different phases of muscular contraction.[157] During the "Huxley Lecture" he stated in retrospect, that he could not imagine a more efficient mechanism to constrict these vessels.[158]

1857 On the flow of the lacteal fluid in the mesentery of the mouse

[edit]His next paper[159] was a short report based on observations that he had made in 1853.[160] This first experiment, as opposed to purely microscope work,[82] determined the nature of the flow of chyle in the lymphatics and whether the lacteals in the gastrointestinal wall could absorb solid granules from the lumen.[82] For the first experiment, a mouse fed beforehand on bread and milk was chloroformed and then had its abdomen opened and a length of intestine placed on glass under a microscope.[82] Lister repeated the experiment several times and each time saw mesenteric lymph flowing in a steady stream, without visible contractions of the lacteals. For the second experiment, Lister dyed some bread with indigo dye and fed it to a mouse, with the result that no indigo particles were ever seen in the chyle.[161] Lister delivered the paper to the 27th meeting of the British Medical Association, held in Dublin 26 August to 2 September 1857.[122] The paper was formally published in 1858 in the Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science.[159]

Seven papers on the origin and mechanism of inflammation

[edit]In 1858, Lister published seven papers on physiological experiments he conducted on the origin and mechanism of inflammation.[162] Two of these papers were research into the neural control by the nervous system of blood vessels, "An Inquiry Regarding the Parts of the Nervous System Which Regulate the Contractions of the Arteries" and "On the Cutaneous Pigmentary System of the Frog", while the third and the principal paper in the series was titled: "On the Early Stages of Inflammation", which extended the research of Wharton Jones.[162] The three papers were read to the Royal Society of London on 18 June 1857.[163] They had originally been written as one paper and had been sent to Sharpey, John Goodsir and the English pathologist James Paget for review.[164] However, Paget and Goodsir both recommended that it be published as three separate papers.[164][165]

1858 An Inquiry Regarding the Parts of the Nervous System Which Regulate the Contractions of the Arteries

[edit]During 1856, Lister has been thinking about the nervous control of blood vessels and had been studying the work of various French researchers who were examining the denervation of the sympathetic nerves.[166] Lister thought that how blood vessels behaved when irritated was important to understand the inflammatory process.[164]

In 1843, Christian Georg Theodor Ruete carried out experiments on the sympathetic and motor nerves to examine the function of the iris, that established a common technique of nerve sectioning,[167] that was used to study the origin of nerves in the spinal canal.[166] In 1852, Ludwig Julius Budge and Augustus Volney Waller used the technique to show that "cervical branch of the great sympathetic are connected with a region of the spinal medulla which lies between the seventh cervical and the second dorsal vertebrae", making it clear that the cervical sympathetic nerve was connected to the 'cerebro-spinal system'.[166] Further research by Budge showed that the sympathetic nerve connected to the eye had its origin in the spinal medulla, while Waller showed how sympathetic nerve denervation could be varied at will.[168] Futher research by Sir Benjamin Brodie and M. Chossat discovered the temperature of the leg rises when the sciatic nerve is cut and that was confirmed by Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard in 1853.[169]

In October 1857, the referee for Philosophical Transactions John Goodsir wrote to Sharpey who warned Lister experiments conclusions were similar to findings by the German physiologist Eduard Friedrich Wilhelm Pflüger.[170] This was to enable Lister to print an acknowledgement.[170] Pflüger found that vasomotor control was through nerve fibres connected to the spinal canal which were similar to Lister research showing vaso-motor fibres came from the spinal canal through the sciatic plexus.[171] Although their approaches were similar, Lister used denervation and discovered that even after parts of the spinal cord were removed, the arterioles eventually recovered their contractility.[171]

The experiments on vasomotor control began in the autumn of 1856 and continued until the autumn of the next year.[171] In total, Lister conducted 13 experiments, some of which were repeated to verify the results of other experiments in the series.[172] He used a microscope fitted with an ocular micrometer, a recent invention, to measure the diameter of blood vessels in a common frogs web. In a before and after experiment, he ablated parts of the central nervous system[173] and also before and after, split the sciatic nerve.[162] Lister concluded that blood vessel tone[d] was controlled from the medulla oblongata and the spinal cord.[175] This refuted Wharton's conclusions, in his paper Observations on the State of the Blood and the Blood-Vessels in Inflammation.[176] who was not able to confirm that the control of blood vessels of the hind legs was dependent upon spinal centres.[177]

These experiments[178] satisfied a contemporary dispute between physiologists concerning the origin of the influence exercised over blood vessel diameter (calibre) by the sympathetic nervous system.[149] The dispute began when Albrecht von Haller formulated a new theory known as Sensibility and Irritability in his 1752 thesis De partibus corporis humani sensibilibus et irritabilibus. The dispute had been debated since the middle of the 18th century. Haller put forward the view that contractability was a power inherent in the tissues which possessed it, and was a fundamental fact of physiology.[179] It concerned the property of irratability, the supposed automatic response of muscular tissue, especially visceral tissue, to external stimulus, that caused them to contract when stimulated.[179] Even as late as 1853, highly respected textbooks, for example William Benjamin Carpenter Principles of Human Physiology stated the doctrine of 'irritability' was a fact beyond dispute,[180] and this was still considered contentious when John Hughes Bennett created the Physiology article for the 8th edition of Encyclopædia Britannica in 1859.[179]

1858 On the Cutaneous Pigmentary System of the Frog

[edit]The second part of the original paper[181] was an experiment into the nature and behaviour of pigment.[182] It had been known for some years that the skin of frogs is capable of varying in colour under different circumstances.[183] The first account of this mechanism had been first described by Ernst Wilhelm von Brücke of Vienna in 1832[183] and later investigated further by Wilhelm von Wittich in 1854[181] and Emile Harless in 1947.[184]

Lister had noted that the beginning of inflammation was always accompanied by a change of colour in the frog's web.[183] He determined that the pigments consisted of "very minute pigment-granules" contained in a network of stellate cells, the branches of which, subdividing minutely and anastomosing freely with one another and with those of neighbouring cells, constitute a delicate network in the substance of the true skin.[183] It had been supposed that the concentration and diffusion of the pigment depended upon the contraction and extension of the branches of the star-shaped cells in which it was contained; and that only these movements of the cells were under the influence of the nervous system. At the time, there was no cell theory of matter nor were there any dyes or fixatives that could used to enhance experimental discovery.[182] Indeed, Lister wrote of this, stating "The extreme delicacy of the cell wall makes it very difficult to trace it among the surrounding tissue".[182] Lister observed that it was the pigment granules themselves and not the cells that moved, and that this movement was not merely brought about by the control of the nervous system, but perhaps by the direct action of irritants on the tissues themselves.[183] He believed that the pigment reflected the activity of blood vessels, though it was the slowing of blood flow that initiated the process of inflammation.[182]

1858 On the early stages of inflammation

[edit]The focal study[185] was the longest paper of the three and the last to be published.[164] Like many of his colleagues, Lister was aware that inflammation was the first stage of many postoperative conditions[186] and that excessive inflammation often preceded the onset of a septic condition.[187] Once that happened, the patient would develop a fever.[187] Lister had come to the conclusion that accurate knowledge of the functioning of inflammation could not be obtained by researching the more advanced stages, which were subject to secondary processes.[188] He therefore started in quite a different way from that of almost all his predecessors by directing his enquiry to the very first deviations from health, hoping to find in them "the essential character of the morbid state most unequivocally stamped".[188] Essentially, Lister performed these experiments to discover the causes of erythrocyte adhesiveness. As well as experimenting on frogs' web and bats wing,[188] Lister used blood that he had obtained from the end of his own finger that was inflamed and compared it against blood from one of his other fingers.[162] He discovered that after something irritating had been applied to living tissues which did not kill them outright, firstly the blood vessels contracted and their lumen became very small; the part became pale. Secondly, the vessels after an interval, dilated and the part became red. Thirdly, some of the blood in the most injured blood vessels slowed down in its flow and coagulated. Redness occurred which, being solid, could not be pressed away. Lastly, the fluid of the blood passed through the vessel walls and formed a "blister" about the seat of injury.[134] He found that each tiny artery was surrounded by a muscle, which enables it to contract and dilate. He found further that this contraction and dilation was not an individual act on its part, but was an act dictated to it by the nervous cells in the spinal cord.[189]

The paper was divided into four sections:

- The aggregation of red blood cells when removed from the body, i.e., which occurs during coagulation.

- This section deals with the aggregation of the cells of the blood, which occurs during the process of clotting. It shows that when blood is removed from the body this aggregation depends on their possessing a certain degree of mutual adhesiveness, which is much greater in the white blood cells than in the red blood cells. This property, though apparently not depending upon vitality, is capable of remarkable variations, in consequence of very slight chemical changes in the blood plasma.[188]

- The structure and function of blood vessels.

- This section shows that the arteries regulate, by their contractility, the amount of blood transmitted in a given time through the capillaries, but that neither full dilatation, extreme contraction, nor any intermediate state of the arteries, is capable per se of producing accumulation of blood cells in the capillaries.[190]

- The effects of irritants on blood vessels, e.g., hot water.

- This section details how the effects are two-fold

- firstly, a dilatation of the arteries (commonly preceded by a brief period of contraction), which is developed through the nervous system and is not confined to the part brought into actual contact with the irritant, but implicates a surrounding area of greater or less extent; and

- secondly, an alteration in the tissues upon which the irritant directly acts, which makes them influence the blood in the same manner as does ordinary solid matter. This imparts adhesiveness to both the red and the white blood cells, making them prone to stick to one another and to the walls of the vessels, and so gives rise, if the damage to the tissues be severe, to stagnation of the blood flow and ultimately to obstruction.[190]

- This section details how the effects are two-fold

- The effects of irritants on tissue.[190]

- The fourth section describes the effects of irritants upon the tissues. It proves that those which destroy the tissues when they act powerfully, produce by their gentler action only a condition bordering on loss of vitality, i.e. a condition in which the tissues are incapacitated, but from which they may recover, provided the irritation has not been too severe or protracted.[190]

Lister's paper was able to show that capillary action is governed by the constriction and dilation of the arteries. The action is affected by trauma,[e] irritation or reflex action through the central nervous system.[162] He noticed that although the capillary walls lack muscle fibres, they are very elastic and are subject to significant capacity variations that are influenced by arterial blood flow into the circulatory system.[162] Drawings made with a camera lucida were used to depict the experimental reactions.[162] They displayed vascular stasis and congestion in the early stages of the body's reaction to damage. According to Lister, vascular alterations that were initially brought on by reflexes occurring within the nervous system were followed by changes that were brought on by local tissue damage. In the conclusions of the paper, Lister linked his experimental observations to physical clinical conditions, for example skin damage resulting from boiling water and trauma occurring after a surgical incision.[162]

After the paper was read to the Royal Society in June 1857, it was very well received and his name became known outside Edinburgh.[136]

On a Case of Spontaneous Gangrene from Arteritis, and on the Causes of Coagulation of the Blood in Diseases of the Blood-Vessels

[edit]Lister's first paper is an account of a case of spontaneous gangrene in a child.[191] The paper on coagulation[192] was read before the Medico-Chirugical Society of Edinburgh on 18 March 1858.[151] In an account written by Agnes, she states that there was no one at the medical school meeting who was capable of appreciating it, and the remarks made upon it were very poor. There were suggestions for improvement which Lister threw out. There was lots of cheering, proclaiming it a great success. The paper was written up at 7pm, with Lister dictating and Agnes writing it during a 50-minute session, followed by the exposition to the society at George Street hall at 8pm.[193]

Lister first used the amputated legs from sheep and discovered that blood remained liquid in the blood vessels for up to six days and still underwent coagulation, albeit more slowly when the vessel was opened. He also noticed that if vessels remained fresh, the blood would remain fluid.[194] In later experiments he moved to cats.[151] He tried to emulate an inflamed blood vessel by exposing the jugular vein of the animal and applying irritants then constricting and opening the flow, to measure the effect. He noticed that in the damaged vessel the blood would coagulate[192][149] He eventually came to the conclusion that if there was ammonia in the blood, it was much less important than the condition of the vessel in stopping coagulation.[151] He tested his hypothesis on three cadavers by examining the condition of various veins and arteries and found he was correct.[195] He also concluded that the Ammonia theory did not apply to vessels in the body, but it could apply to blood outside the body. While that was incorrect, his other conclusions were accurate.[151] Specifically that inflammation in the blood vessel lining, results in coagulation occurring.[67] Lister realised that vascular occlusion increased the pressure through the network of small vessels, leading to the formation of "liquor sanguinis"[f] that lead to further localised damaged perfusion.[67] Certainly, Lister had no knowledge of the coagulation cascade but his experiments contributed to the current understanding of clotting,[149] the final product of coagulation.

Lister continued experimenting in April, examining vessels and blood from a horse. This resulted in another communication to the society on 7 April.[151] His work in coagulation continued until the end of the year. Lister's second article on coagulation was published in August 1958, and was one of two case histories he published in the Edinburgh Medical Journal in 1858.[196] Titled: "Case of Ligature of the Brachial Artery, Illustrating the Persistent Vitality of the Tissues".[197] The history described saving a patient's arm from being amputated which had been constricted by a tourniquet for thirty hours.[191] The second history was titled "Example of mixed Aortic Aneurysm" and published in December 1858.[198]

1858 Preliminary account of an inquiry into the functions of the visceral nerves

[edit]Lister continual interest in the nervous control of blood vessels led him to conduct a series of experiments during June and July 1858, where he researched the nervous control of the gut.[196] The research was published in the form of three letters sent to Sharpey. The first two letters were sent on 28 June and 7 July 1858[199] The last letter was published as the "Preliminary Account of an Inquiry into the Functions of the Visceral Nerves, with special reference to the so-called Inhibitory System.".[200]

He had been studying the work of Claude Bernard, LJ Budge and Augustus Waller and had become interested in what was known as "sympathetic action", where inflammation appeared in a different area from the source of irritation.[201] This led him to study Pflüger's 1857 paper titled "About the inhibitory nervous system for the peristaltic movements of the intestines",[202] proposed that the splanchnic nerves instead of exciting the intestine muscle layer that they are connected to, inhibit their movement.[196] The German physiologist Eduard Weber made the same claim.[196] Pflüger had named these inhibitory nerves "Hemmungs-Nervensystem", a name that Syme, at Lister's request thought they should be translated as inhibitory nervous system.[203] Lister dismissed Pflüger's idea of inhibitory nerves as not only implausible but not supported by observation,[204] as a mild stimulus caused increased muscle activity which changed to a decreased muscle activity as the incoming stimulus became stronger.[204] Lister believed that it was questionable whether the motions of the heart or the intestines are ever checked by the spinal system, except for very brief periods.[204]

Lister conducted a series of experiments using mechanical irritation and galvanism to stimulate the nerves and spinal cord in rabbits and frogs.[204] and due to rabbits active gut movement, he considered them ideal for the experiment.[205] To ensure their gut reflexes were not impaired, the rabbits were not anaesthetised.[149] Lister conducted three experiments. In the first experiment, an incision was made in the rabbit's side and a section of intestine was pulled through the skin. Lister then connected a magnetic coil battery to the splanchnic nerves in the spinal cord. When the current was applied, the gut completely relaxed but when the current was applied locally, a small localised contraction occurred that did not spread to the bowel.[149] Lister stated that "this observation is of fundamental importance, since it proves that the inhibitory influence does not operate directly upon the muscular tissue, but upon the nervous apparatus by which its contractions are, under ordinary circumstances, elicited".[200] In the second experiment, Lister examined the reaction in a section of the bowel, when he restricted the blood supply by tying the vessels and found that there was an increase in peristalsis. When he applied current the gut relaxed. He concluded that activity in the gut was under the control of bowel wall nerves and had been stimulated due to loss of blood.[200] In the third experiment he removed the nerves from a section of the bowel while ensuring to maintain a good blood supply. This time, stimulation of the section had no effect except when the section would spontaneously contract.

During the histological study of the bowel wall, Lister discovered a plexus of neurons[205] the myenteric plexus, that confirmed the observations made by Georg Meissner in 1857.[206][207]

Lister concluded, "...it appears that the intestines possess an intrinsic ganglionic apparatus which is in all cases essential to the peristaltic movements, and, while capable of independent action, is liable to be stimulated or checked by other parts of the nervous system".[204]

Although Lister did not believe in the inhibitory system, he did conclude that extrinsic nerves controlled the intestinal motor function indirectly through their effect on the plexus. It was not until 1964 that this was proven by Karl‐Axel Norberg.[208]

Notice of further researches on the coagulation of the blood

[edit]Lister's third paper on coagulation[209] was a short article in the form of a communication consisting of five pages that were read before the Medico-Chirugical Society of Edinburgh on 16 November 1859. In the paper, Lister found that the coagulation of blood was not solely dependent on the presence of ammonia, but may also be influenced by other factors. In a demonstration before the society, Lister had a sample of horse's blood that had been shed twenty-nine hours earlier and added acetic acid to it. The blood remained fluid despite being acidified, but it eventually coagulated after being left to stand for 15 minutes. Lister demonstrated that the Ammonia theory was incorrect as the coagulation of the blood was not dependent on the presence of ammonia. He concluded that other factors may influence blood coagulation in addition to or instead of ammonia, and that the Ammonia theory was fallacious.[209]

Glasgow appointment

[edit]On 1 August 1859, Lister wrote to his father to inform him of the ill-health of James Adair Lawrie, Regius Professor of Surgery at the University of Glasgow, believing he was close to death.[210] The anatomist Allen Thomson had written to Syme to inform him of Lawrie's condition and that it was his opinion that Lister was the most suitable person for the position.[211] Lister stated that Syme believed he should become a candidate for the position.[210] He went on to discuss the merits of the post; a higher salary, being able to undertake more surgery and being able to create a bigger private practice.[210] Lawrie died on 23 November 1859.[212] In the following month, Lister received a private communication, although baseless, that confirmed he had received the appointment.[213] However, it was clear the matter was not settled when a letter appeared in the Glasgow Herald on 18 January 1860 that discussed a rumour that the decision had been handed over to the Lord Advocate and officials in Edinburgh.[214][213] The letter annoyed the members of the governing body of Glasgow University, the Senatus Academicus. The matter was referred to the Vice-Chancellor Thomas Barclay who tipped the decision in favour of Lister.[215] On 28 January 1860, Lister's appointment was confirmed.[30]

Glasgow 1860–1869

[edit]

University life

[edit]To be formally inducted into the academic staff, Lister had to deliver a Latin oration before the senatus academicus.[216] In a letter to his father, he described how surprised he was when a letter arrived from Allen Thomson informing him that the thesis had to be presented the next day on 9 March. Lister unable to start the paper until 2 am that night, had only prepared around two-thirds of it, when he arrived in Glasgow. The rest was written at Thomson's house. In the letter, he described the dread he felt being admitted into the room prior to presenting the oration. After the thesis was read and Lister was inducted to the senate, he signed a statement not to act contrary to the wishes of the Church of Scotland.[217] While the contents of his thesis have been lost, the title is known, "De Arte Chirurgica Recte Erudienda" ("On the proper way of teaching the art of surgery").[218]

In early May 1860, the couple made the journey to Glasgow to move into their new house at 17 Woodside Place, at the time on the western edge of the city.[216] In 1860, university life in Glasgow was lived in the grimy quadrangles of the small college on Glasgow High Street, a mile east of the city centre next to Glasgow Royal Infirmary (GRI) and the Cathedral and surrounded by the most squalid part of the old medieval city.[219] The Scottish poet and novelist Andrew Lang wrote of his student days at the college, that while Coleridge could smell 75 different stenches during his student days in Cologne, Lang counted more.[219] The city was so polluted the grass did not grow.

The position of Professor of Surgery at Glasgow was peculiar, as it did not carry with it an appointment as surgeon to the Royal Infirmary, as the university was separate from the hospital. The allotment of surgical wards to the care of the Professor of Surgery depended upon the goodwill of the directors of the infirmary.[220] His predecessor Lawrie never held any hospital appointments at all.[221] Having no patients to care for, Lister immediately began a summer lecture course. He discovered that college classrooms were considered too small and had low ceilings for the number of students, which made them unpleasant to be in when filled to overcrowding.[219] Before his first lecture, the couple cleaned and painted the dingy lecture room assigned to them, at their own expense.[219] He inherited a large class of students from his predecessor that grew rapidly.[219]

After his first session, he wrote favourably of Glasgow:

The facilities I have here for prosecuting this course as compared to the difficulties I laboured under in Edinburgh are quite delightful – museums, abundant material and a good library all at my disposal and my colleague Allen Thompson co-operating in the kindest and most valuable manner[222]

In August 1860, Lister was visited by his parents, who took a "saloon" carriage on the Great Northern Railway.[223] In September 1860, Marcus Beck came to live with the Listers and their two servants, while he studied medicine at the university.[223] In the closing weeks of the summer, the Listers along with Beck, Lucy Syme and Ramsay went on a short holiday to Balloch, Loch Lomond. While the group was visiting Tarbet, Argyll, the men rowed across the loch and ascended Ben Lomond.[224]

Election to surgeoncy

[edit]In August 1860, Lister had been rejected for a post at the Royal Infirmary by David Smith, a shoemaker who was the chairman of the hospital board.[225] When Lister put his case to Smith explaining the need for anatomical demonstrations so the students could understand the practice of surgery, Smith stated his belief that "the infirmary was a curative institution, not an educational one".[7] The rejection both annoyed and surprised Lister as he had been promised by Thomson that the position was assured.[224] Indeed, he had informed his father of the fact that the post was guaranteed in his letter to his father.[225]

In November 1860, the winter lecture course began. In total 182 students registered for the lectures[226] and according to Godlee it was likely the "largest class of systematic surgery in Great Britain, if not in Europe".[226] The class consisting of mostly 4th year students with some 3rd and 2nd year students, was so enthused, that they decided to make Lister the Honorary President of their Medical Society.[224] When the time approached for the election to the surgeoncy in 1861, 161 students signed a petition on parchment supporting his claim for election.[226] Lister was not elected until 5 August 1861, in what was described by Beck as a "troublesome canvas".[227] Lister was put in charge of wards XXIV (24) and XXV (25) in October 1861.[228] It wasn't until November 1861 that he performed his first public operation.[229] Soon after Lister arrived at the GRI, a new surgical block was built and it was here that he conducted many of his trials of antisepsis.[230]

Holmes System of Surgery

[edit]Between the end of his winter lecture course and his appointment, Lister's correspondence contained little of scientific interest. A letter to his father dated 2 August 1861 explained why.[231] He had halted his experiments on coagulation to work on two chapters, "Amputation" and "On Æsthetics" (On anaesthetics) for the medical reference work System of Surgery by Timothy Holmes, published in four volumes in 1862.[232] Chloroform was Lister's preferred anaesthetic.[233] He wrote three papers for Holmes in 1861, 1870 and 1882.[234][235] The science of anaesthesia was in its infancy[236] when Lister first recommended chloroform to Syme in 1855, and he continued to use it until the 1880s.[227] His sister Isabella Sophie first described it to him in 1848 when she had a tooth pulled. He had also used it without complications on three patients with tumours of the jaw in 1854.[233] He classed it along with alcohol and opium as a "specific irritant" in "On the early stages of imflammation".[233] Lister preferred it to ether, as it was safer to use in artificial light, protected the heart and blood vessels, and, Lister believed, gave the patient "mental tranquility" as it was the safest.[227] In the 1871 edition, he reported that there had been no deaths in the Edinburgh or Glasgow infirmaries from chloroform,between 1861 and 1870.[227] Lister described how his assistant applied the chloroform onto a simple handkerchief used as a mask and watched the patient's breathing. In 1870 however Lister updated the chapter to state that he felt apprehension about using chloroform on the "aged and infirm".[227] In the same edition he recommended nitrous oxide for tooth extraction and the use of ether to avoid vomiting after abdominal surgery. In the winter of 1873, the English medical journals reported that sulphuric ether should be used instead but Watson Cheyne stated there had been no deaths from chloroform during the winter of 1873. In 1880, the British Medical Association recommended the synthetic gas ethidene dichloride for clinical trials. On 14 November 1881, Paul Bert published the dose-response curve of chloroform but Lister believed that smaller doses were sufficient to anaesthetize the patient.[237] Starting in April 1882, Lister first conducted clinical research using ether and from July to November, lab experiments on chaffinches and then on himself and Agnes, to determine the correct dose.[238] The 1882 chapter continued to recommend chloroform.[238]

The chapter on amputation was much more technical than the anaesthesia chapter, for example describing the ways of cutting the skin to produce flaps to close over the wound.[g][239] In the first edition, Lister examined the history of amputation from Hippocrates to Thomas Pridgin Teale, William Hey, François Chopart, Nikolay Pirogov and Dominique Jean Larrey[240] and the discovery of the tourniquet by Etienne Morel.[122] In the first edition, Lister devoted seven pages to dressings, but by the third edition used only a single sentence to recommend a dry dressing[241] as opposed to the more common water dressing, thought to excluded air.[242] By the third edition, Lister focused on describing three innovative surgical techniques. The first was a method for amputation through the thigh that he developed between 1858 and 1860, a modification of Henry Douglas Carden's technique for knee amputation.[240] The thigh amputation went through the femoral condyles in a circular fashion with a small posterior flap that enabled a neat scar.[243]

The second technique was an aortic tourniquet for controlling blood flow in the abdominal aorta.[240] The vessels of the aorta were too tough to close properly and ligatures either damaged the artery walls or caused premature death if left in too long.[238] The third technique was a method of bloodless operation that he created in 1863–1864 by elevating a limb and quickly applying an india rubber tourniquet to stop limb circulation.[244] It became unnecessary with the use of the Esmarch bandage.[122] In 1859, he advocated for the use of silver wire sutures that had been invented by J. Marion Sims, but their use fell out of favour with the introduction of antiseptics.[240]

Croonian Lecture

[edit]On 1 January 1863, Lister returned to the topic of coagulation with the Croonian Lecture titled "On the coagulation of the blood",[245] although it contained little that was new.[246] The lecture, given in London at the invitation of the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians,[191] began by reconfirming the fallacious nature of the ammonia theory, instead proposing that shed blood coagulates when the solid and fluid elements of the blood meet. His experiments had confirmed that blood plasma (liquor sanguinis) alone does not coagulate, but does when in contact with red blood cells.[67] Lister suggested that living tissues possessed similar properties in relation to blood coagulation. He mentioned the presence of coagulable fluid in the interstices of cellular tissue and described instances of oedema liquid coagulating after emission, possibly due to a slight admixture of red blood cells.[245] Lister highlighted the tendency of inflamed tissues to induce coagulation in their vicinity, suggesting that inflamed tissues temporarily lose their vital properties and behave like ordinary solids, leading to coagulation. He provided examples of inflamed arteries and veins exhibiting coagulation on their interior, like artificially deprived vessels.[245] Lister then noted that inflamed tissues induce coagulation and oedema effusions remain liquid. He hypothesised that the accumulated red blood cells increased pressure in inflamed capillaries and contributed to the loss of healthy condition in capillary walls, leading to coagulation.[245] In closing, Lister said his previous microscopic investigation published in the Philosophical Transactions, supported the view that tissues could be temporarily deprived of vital power by irritants. He proposed that inflammatory congestion arose from the adhesiveness of red blood cells to irritated tissues, like their behaviour outside the body when encountering ordinary solids. In finishing the lecture, Lister said he was satisfied that his previous conclusions on the nature of inflammation were independently confirmed through his research into blood coagulation.[245]

On excision of the wrist for caries